As foster parents try to serve and support the children in their care, finding the right resources and services for them to thrive academically can be a challenge. With school back in session, students may be experiencing challenges in the classroom as they transition to new schools, new teachers, new routines. It is not uncommon that children in foster care may be behind academically in some ways. There are multiple factors that can be at play.

Educators are heroes! Working hard every day to serve, support, and teach our children. Foster children today are the bankers, doctors, teachers, and policy makers of tomorrow. We want them to have every opportunity to thrive, to have the potential for a full and meaningful life. It is crucial that we give them the tools and teach them the skills to be successful.

Foster parents can play an important role in advocating for their children’s academic resources and supports. They can work collaboratively with schools as an advocate for their child’s success. That doesn’t mean that it is easy or that a solution can be found overnight.

On this #FosterFridayLive, Carlos Littlejohn, SC Elementary School Principal, is going to help us understand the roles that each of us can play in supporting the academic (and holistic) success of students that have experienced trauma. He has been the principal at Rice Elementary School for four years and has been an educator for 19 years.

How Can SC Educators Support Kids in Foster Care?

One of the things that we’ve intentionally done is take the extra effort to know all our children and their families. I would say that I know roughly 99% of these children- still trying to get to know the Kindergarteners. I know the children as well as their families. I intentionally, as principal, try to get to know all these children. That way when there is a situation, I can respond accordingly. Everything is on a case-by-case basis, child-by-child basis. You have to be able to respond accordingly. We tell our teachers all the time, make sure you form a relationship with these children and their families. Naturally, you’re here to teach these children, but if you don’t know them, your instruction goes out the window any way. Having a relationship makes a difference.

It’s all about forming a relationship. The more you know about a child, the more you can understand where the child is coming from and be able to respond [to behaviors] accordingly. For example, one of the things that we talk about incessantly that is not a big deal is homework. Naturally homework just reinforces what is taught in class, but to me, homework is not that big of a deal. The more that child gets to know in class, the more you teach that child in class, the more you realize- instead of a child doing 20 problems a night, five is good enough. Yeah, just harping on the importance. Once you know and understand where a child is coming from, it’ll take you very far. That child will respond to you accordingly. We intentionally tell our teachers to make sure they get to know families because if you don’t know who you serve, you’re not going to be able to serve them anyway. To me, that’s one of my mantras. You have to know your children before you can teach your children.

How does trauma and transition impact a child’s academics?

A lot of things carry over from home to the school. Some children you can readily identify something’s wrong. Some you can’t because they try to mask it, to hide it, but it all comes out anyway in terms of how they perform in school. So, it’s about those relationships. I tell teachers all the time, if you notice a child is in peril so-to-speak, if the child has come in and he or she is not acting their typical self, ease up first of all in your response. Also, be an outlet for the child. If the child is going to talk, listen. Respond accordingly. If the child is giving too much information, tell an administrator. Of course, we will step in and respond accordingly. It’s all about relationships.

I’m very intentional and strategic in my relationships with the teachers and the children. I always say that I deal with five sets of personalities: teachers, children, parents, district office personnel, and the community. I’m strategic in how I respond to everybody; but to me, it is the children first. So again, I tell the teachers, it takes a village. We are a village. We aren’t with them 24 hours, but while they’re here for eight hours a day, we have to be the village for these children.

How can foster parents work collaboratively with the school to support their children?

At our school, we have quite a few resources. In addition to the administrative team, we have a guidance counselor, a mental health counselor, a school psychologist. We have a gamut of resources. We have an open door policy. Any time there is a concern, by all means, please voice that concern to who you believe to be the right person. We intentionally try to respond. We’re intentional. The key word, the buzz word is “intentional.” We know that the more we know about a child that is experiencing trauma or difficulty, the better we can point the parent in the right direction. We’re advocates for all the children and the parents as well. Again, the open door policy means that we’re going to try to get you in the right direction.

Setting up a conference with the teacher at the beginning is a good place to start. Just be candid and forthright with the information. That teacher is going to respond accordingly even if it means finding additional resources for that family or that child – in the building, out of the building. Some schools don’t have that open door policy. Start with the teacher initially and build that relationship- giving them as much information as he or she needs to be able to respond accordingly.

I want my students’ parents to start with the teacher. Let the teacher do a little bit of data collection. The data speaks for itself. If that isn’t sufficient, that’s not working, talk to the administrator- the principal or assistant principal, and they should guide you in the right direction. I can’t speak for other schools, but here we want you to form a relationship with the teacher first and let them do as much as they can at that particular time. Again, if that’s not sufficient, take it to the administrator. We wouldn’t be doing you due diligence if we didn’t assist you in getting what you need.

What resources can you recommend foster parents seek on behalf of their students if they are struggling in school?

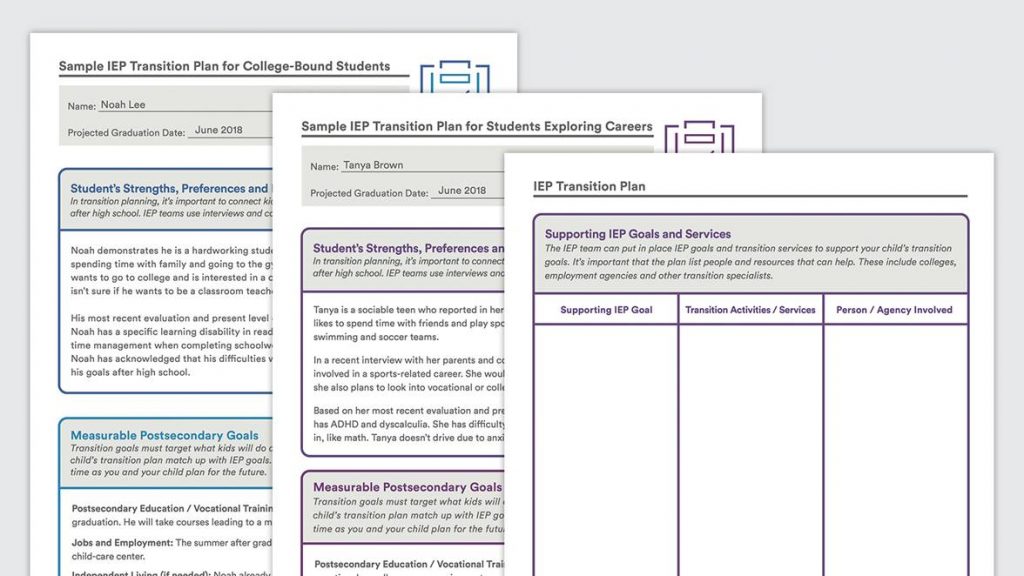

There are the people resources we’ve talked about, but beyond that there are several mechanisms in place. There is the IEP- Individualized Education Plan. There are a series of steps that you have to go through for a child to get an IEP- testing, data collection. There is also a 504 Plan which is not as stringent as an IEP. You still get accommodations and modifications, but it isn’t as stringent. The child is crying out for help, we’re going to do whatever it takes for a child to get some help. Granted, with the IEP and 504, there are a series of steps. It’s not going to happen overnight. If the parent has the necessary documentation from the pediatrician, that’s helpful but you have to realize that it is two different diagnoses. There is the medical diagnoses, but then you have to get the school’s assessment for necessary accommodations and modifications.

Again, there are the guidance counselor and mental health counselor. Whatever avenue we need to go on to make sure the child gets help, we’re going to do that.

What is one piece of advice that you would give a foster parent trying to advocate for their child?

First and foremost, I would readily say, let the administrator know as much information as possible, as you’re allowed, so that as much as can be done, the child can get the necessary help. Give the teacher some time to get to know the child. Give the administrators time to get to know the child as well. I am a firm believer that once that relationship is formed, the more we know, the better off everyone will be in helping the child. Putting the child first is ultimately the key to this entire deal.